‘Second Screen’ for Health Care Messaging: Looking for Lessons from #CancerFilm By Sally James

PLOS SciComm blog invited health and science journalist Sally James to write this post exploring lessons for science communicators learned from the large scale social media campaign mounted for the PBS documentary TV series, “Cancer, The Emperor of All Maladies.” — Victoria Costello, PLOS Senior Social Media & Communities Editor

For three nights this Spring, an unusual set of fireworks exploded across the social media landscape with implications for public discussions of health, particularly for health care professionals whose work includes crafting messages for patients.

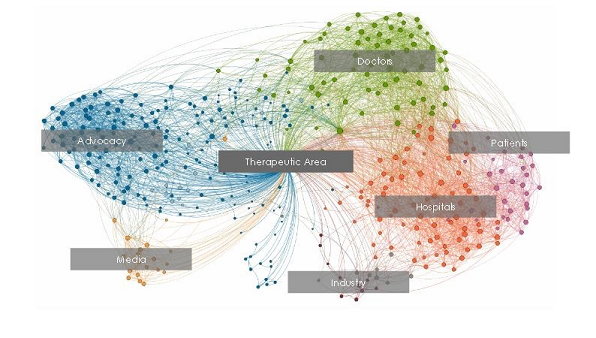

An estimated 746 doctors joined in a twitter chat with the hashtag #cancerfilm in an extended conversation with more than 500 self-described patients, as well as about 12,000 other people who didn’t fit either of those labels (but fit 13 other categories.) This three-night, multiplayer dialogue began March 31 and created an “unprecedented” event according to one data junkie, Audun Utengen, of Symplur, LLC. Utengen runs the site www.symplur.com, which provides analytics on healthcare related hashtags.

The jury is still out on whether others will imitate this episode of what is called the “second screen” phenomena in health care. Sports and music fans already tweet comments to each other while athletes and musicians are performing. “Did you see that goal?” But what happened on the three consecutive nights – beginning March 31, was a formal invitation by the US National Cancer Institute (and 18 partner research organizations) for the public to “comment” while watching a public television documentary entitled, “The Emperor of All Maladies,” about cancer.

“This opens up a whole new area for conversation in health care,” Utengen said in an interview. “This was an explosion of people talking about a disease.”

Emperor was a six-hour major television event on the US Public Broadcasting System, PBS, presented by documentary filmmaker Ken Burns, in partnership with WETA, based on the 2010 Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Siddhartha Mukherjee.

Cancer – in the documentary – was portrayed in lethal reality, complete with historic explanations of mistaken ideas and misguided treatments and days when wards full of children faced almost certain death. Some of those on Twitter literally wrote “I’m turning it off now” because they said it was too difficult to watch. Utengen himself, whose family has been touched by pancreatic cancer, said it was not easy to see some images.

But the authenticity pleased some of the patients watching, who tweeted things like, “That’s exactly how I felt during chemotherapy” or “I remember losing my hair.”

For those who wish to study it, the entire transcript of #cancerfilm is available here. You must scroll to the bottom to set parameters for the time section you wish to read. One social scientist who has been studying social media said parsing the importance from of an event like this is a statistical nightmare. Devin Gaffney is a doctoral student at Northeastern University in Boston, who has studied social media’s role in political uprisings, for example.

He said linking “online” conversation to offline behavior for #cancerfilm is tricky. “I think very likely there is a real link there – attention online will likely lead to some degree of attention (and donations, and attitudinal shifts, and improved science literacy), but I don’t think it happens in a way that we can directly quantifiably measure.” Surveys done months later might be able to pick up an impact, he explained.

During #cancerfilm some researchers posted inspiration and resolve, and even humility when facing new discoveries. Big pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb and Celgene, were also tweeting. They were joined by research institutes, such as Memorial Sloan-Kettering and University of California at San Francisco, UCSF. Some of the tweeting provided information on therapies that were discussed inside the documentary itself.

The presence of research institutes tweeting about themselves drew this sharp rebuke from journalist and science communications expert Paul Raeburn.

Other critics of the conversation pointed to a lack of discussion of prevention, and what some called too much hype about new avenues of treatment, especially immunotherapy.

Peter Garrett is the director of communications for NCI, and he saw the six hours of the documentary as an opportunity for outreach. The film was a rare platform for putting information about cancer into the stream of discussion exactly while questions emerged for the audience watching, he explained in a phone interview.

The NCI worked diligently to prepare and lead the event and have materials ready to post, Garrett said. Utengen counted 35 federal agencies tweeting during the event. *

A Platform for Online Patient Health Care Communities

Media relations expert Greg Matthews* believes the social media explosion of #cancerfilm will inspire others to attempt to re-create it. “Anyone who saw the impact that #cancerfilm had on the online health ecosystem is going to be building on that model – it was phenomenally successful,” he wrote in an email.

Matthews works for W20 Group, a marketing consulting company based in Austin, Texas, that publishes detailed reports on social media in health care. Their “Social Oncology Report,” based on 2014 data was published in May.

What made the explosion of conversation so big, Matthews said, was the fertile ground already plowed by the myriad health-care patient communities on twitter. These communities fueled the second-screen event, because they already had online fluency about cancer, he said.

If you aren’t familiar, these are communities often run by patients where people gather weekly to talk about diseases during a certain time slot. Two very active chats are #lcsm and #bcsm. Lung Cancer Social Media (lcsm) includes both doctors and patients and is frequently co-moderated by Seattle patient Janet Freeman-Daily. The breast cancer social media chat was co-founded by a surgeon, Deanna Attai of Burbank, Calif. In network mapping done by researchers of social media, Freeman-Daily and Attai, appear “central” to discussions in their respective disease areas.

During the May conference of the American Society of Clinical Oncology** in Chicago, doctors presented research about how some of these hashtags may operate in influencing patient decision-making, but the research is not published yet.

What Matthews finds interesting is how “chat” communities are changing and becoming more diverse, including patients, providers, advocates, researchers and health policy wonks. His company tracks what he calls more than 500,000 “online identities” related to health care internationally. For his clients, which can include physicians, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies and others, he gathers analytics on how their target audiences behave online, and where the clients may reach a given audience with a message.

“I get the point of critics,” he explained, who see health-care social media as just one more place for marketing of products, devices and branding institutions. “I understand the skepticism. But we know that emotion is a big part of health, and hope is one of the most powerful emotions.”

Hope is a frequent theme of disease-related discussions. Freeman-Daily, for example, is one of the most prominent patient influencers on social media about lung cancer. Her message is: even if you are diagnosed with advanced cancer and given very few treatment options, there may be a clinical trial you could enter.

In her own case, she is currently not showing any evidence of disease, after finding a trial specifically aimed at her cancer’s genomic signature and receiving chemotherapy though a Colorado laboratory.

She is also fighting stigma (as she explains in video link) that she blames on people mistakenly believing this cancer is only suffered by those who are smokers. An estimated 10-15 percent of lung cancer is diagnosed in “never smokers.”

One of Freeman-Daily’s comments during #cancerfilm reflected some of what Matthews observed. Hope is precious.

Nobody seems able to explain what the explosion of conversation could yield in terms of a permanent impact. But the fireworks leave a lingering smoke behind. Someone may learn how to read the signal in that noise.

June 9, 2015 Corrections: the association name for American Society of Clinical Oncology**; and misspelled name for Greg Matthews*. Clarification*.

Sally James has a long career as a medical and science writer for the public, including work at newspapers and magazines. She blogs here, but also reviews the work of others at HealthNewsReview.

Sally James has a long career as a medical and science writer for the public, including work at newspapers and magazines. She blogs here, but also reviews the work of others at HealthNewsReview.

“Hope is not a strategy.” Hype is the fuel for all things web and social media. I am a pro marketer and communicator and the data I have seen says the web is a waste for changing behavior. Social media even more so.

professionals and esp where healthcare or any other exert services are involved, demands evidence basis and double-blind, peer-reviewed roof of efficacy.

I am not seeing that in any of this kind of pop promotional stuff. Let’s see the data!

Great capture of a still-echoing conversation. I confess that after watching the first two hours of “Emperor of All Maladies” I was so angry that I waited a week to watch the remaining four hours on my DVR.

In and amongst all the “hero researchers” and “brave patients” and “generous benefactors” … NO, as in ZERO, mention of the massive industry that cancer treatment is. What’s the likelihood that Cancer Inc. is interested in actually finding cures, if it means losing the firehose of revenue that treatment delivers? And, since cancer is essentially evolution (mutation) happening within the human body, what’s the real hope of “cure” anyway?

Those are questions that #cancerfilm didn’t even mention …

This is a great article, Sally, thank you. Team NCI is very pleased that we were able to help support an online discussion around PBS’s terrific documentary. Given the interest in immunotherapy, we felt it made sense to follow the television airing with a Twitter chat on the topic, and it appears that was also well received.

Cancer is such a horrible disease that affects so many of us, yet we are still amazed at the “…explosion of people talking about a disease,” as you quoted Auden Utengen of Symplur, around the Mukherjee-Burns-Goodman television collaboration.

At NCI we think a lot about how much science and health information is available to consumers, and in communications we recognize that the abundance and complexity of the information about cancer can be overwhelming, and run counter to a traditional public health approach – simple, consistent messaging.

That’s why social media can be so helpful, because it gives consumers the opportunity to ask questions of experts and interact with others. I believe that the Emperor collaboration could very well be a model for the “next gen health campaign.”

I hope we have all learned some helpful lessons about how we can both communicate with and engage with the cancer communities from our #CancerFilm social media experiment,. There was a wealth of healthcare information from 18 partners and an engaged and diverse audience of patients, researchers and clinicians on social media (Twitter) showing how the marriage of the “big screen/small screen” opens up a whole new area for healthcare conversations.

Stay tuned – we are always trying to find ways to innovate, and we will have a lot to say once the NCI-MATCH trial opens in July.

Peter Garrett, @GarBob2

Glad to read these first comments, and happy to respond here.

As far as what Casey has written, I agree that the documentary was oriented toward the book’s point of view – which I would summarize as pro-research. There were episodes in the book revealing less-than-laudable motives on the part of some, but it wasn’t attempting to ask the financial questions you are asking.

Thinking about health literacy, the online conversation you chronicle illustrates health literacy as a social construct, rather than simply ability to read and understand medical and insurance documents. Health information must be interpreted and integrating into complex everyday lives. This happens not in a doctor’s office, but “around the kitchen table”. NCI’s #CancerFilm made the table very big, and included experts more approachable without the white coats. A downside is a likely increase in the knowledge gap between those who have the wherewithal to be at the table and those who do not.

Contemplating health and fitness literacy, the web based chat a person explain shows health and fitness literacy as a sociable assemble, rather than purely power to examine in addition to fully grasp professional medical in addition to insurance policy documents. Well being info should be viewed in addition to establishing in sophisticated every day existence. This particular comes about not necessarily in a doctor’s company, although “around your kitchen table”. NCI’s #CancerFilm manufactured this desk quite massive, in addition to incorporated professionals more approachable with no whitened coats. A new drawback is often a likely enhance within the know-how space in between whoever has this wherewithal to be with the desk and the ones whom usually do not.

Thankyou Sally for sharing such nice event with lots of information, actually I went into tears because my friend died with blood cancer and he was a true friend. I’m thankful to these researchers who keep searching new ways to fight cancer, these researches gave my friend hope of life every time he felt pain and when there was no hope. I’m now visiting cancer hospitals to visit cancer patients and my visit and gifts make them smile, I only visit to see those smiles. Keep sharing these events, I’m looking for more. Good luck.

Thanks Sally for this wonderful piece. I know it was published years ago, but I only watched the documentary “Cancer, The Emperor of All Maladies” recently through Netflix. I must agree with others that it’s a bit hard to watch. Cancer is a nasty disorder, and I can only imagine the efforts of those who are tirelessly looking for the cure. I have a doctor friend who is planning to specialize on oncology, and I know some people close to me who died from cancer. It’s a long way to go, but the docu and social media can help us move one step closer toward more productive healthcare c onversations.

Trivia: Edward Herrmann, the narrator in the said docu, died from a brain tumor. Cancer is a monster.

Thanks Lui. The message about how communities share science literacy is still relevant. I’m glad to hear you liked it.

I’m sorry to hear about your friend. But glad that you enjoyed reading.

What do you think Sally regarding “” Truth About Cancer” documentary?

Have not seen it yet.

Contemplating health and fitness literacy, the web based chat a person explain shows health and fitness literacy as a sociable assemble, rather than purely power to examine in addition to fully grasp professional medical in addition to insurance policy documents. Well being info should be viewed in addition to establishing in sophisticated every day existence. This particular comes about not necessarily in a doctor’s company, although “around your kitchen table”. NCI’s #CancerFilm manufactured this desk quite massive, in addition to incorporated professionals more approachable with no whitened coats. A new drawback is often a likely enhance within the know-how space in between whoever has this wherewithal to be with the desk and the ones whom usually do not.

Sally, I just want to say a bunch of thanks for sharing this factual information. Cancer is more like epidemic nowadays. One of my cousin died of cancer last year. He was diagnosed in the last stage, so he only managed to survive for 6-8 months. Looking for more informative articles like this.

Very informative article. Massage helps to relax the muscle and it relieves pain. Not only massage is sufficient for back pain, you have to follow a few things such as use a good mattress, change your sitting position, avoid lifting heavy objects, do exercise regularly etc.

Thank you very much for this valuable article.

I was in anticipation concerning this topic but i wasn’t disappointed at all.. Sorry about your friend.

Your article about ‘second-screen-for-health-care-messaging-looking-for-lessons-from-cancer film’ looks very great and helpful. Thank you for sharing it.