‘Does that mean you’re not a scientist anymore?’ Getting Science Communication Right By Sam Illingworth

PLOS BLOGS welcomes Sam Illingworth, a professor of physics and science communication, with this guest post. Read his full bio below.

By Sam Illingworth

This is a snippet from a recent dinner party conversation:

Random: So, what job do you do?

Me: I’m a university lecturer

Random: Cool, what in.

Me: Science communication.

Random: What now?

Pause

Me: Science communication.

Random: And what is that exactly?

Me: Well, it’s kind of a new field. Basically it looks at how scientists can better communicate their research to each other and the rest of society, and why they should do so.

Random: But I thought you had a PhD in Atmospheric Physics or something.

Me: I do.

Random: So why aren’t you a lecturer in that?

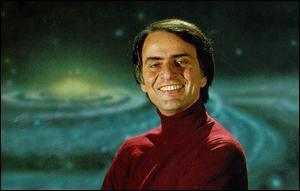

Me (defiantly): Because I believe that this is a field of research that is of great potential benefit to a large number of people. As the great American astronomer Carl Sagan once said, “Science is an absolutely essential tool for any society. And if the scientists will not bring this about, who will?”

Random: So does that mean that you aren’t a scientist anymore?

Pause

Me (meekly): I also teach physics.

I won’t bore you with the rest of the conversation, the point is that this it is a handy microcosm for how some people view science communication, and science communicators in general. Not everybody is as blunt as my dinner companion, but there is no doubt that some science communicators are made to feel undervalued and under appreciated.

The extent to which this is true became evident during a recent session that I convened at the European Geoscience Union’s 2015 general assembly. During a discussion with the audience, those who identified themselves as science communicators indicated that they were sometimes made to feel second-rate, either by more traditional research scientists, or by people who did not understand what it was that they did.

When asked why they thought this was the case, one of the reasons given was that science communication is perceived as being easy; that you turn up to a school, a science festival, a café etc., deliver a speech and then simply move on to the next activity.

This is quite clearly not the case, but from my own personal experience in the field, this does sadly seem to be the view held not only by some scientists, but also by some members of the general public. Someone else in the audience pointed out that this was similar to the inaccurate view that professors ‘just teach’. The reality of course is that teaching is an enormously difficult job that can be made to look easy by people who are very good at their jobs (an issue that is explored further in this journal article).

And so it is with science communication. Perhaps the best way to demonstrate how difficult it can be to communicate science in the right way is to look at how easy it is to get wrong. In recent years there have been many examples of questionable science communication, from the inconvenience caused in the UK by the Met Office’s ‘BBQ summer scandal’, to the trial of the six Italian scientists for their inability to effectively communicate the risk of the L’Aquila earthquake. Like other areas of science, science communication isn’t something that just happens; it requires careful planning, dedication and practice.

Ironically enough, as a community we are quite poor at communicating our successes, but this is what we need to do if we hope to be treated with parity. Ultimately though we should try to not let it get to us. Anyone who has seen the eyes of a child light up as they are introduced to the majesty of science, or who has helped to connect and empower a previously estranged member of society via the medium of science will know that this is enough.

I like to think that if I went to the same dinner party again, the conversation would go a little bit more like this:

Random: So does that mean that you’re not a scientist anymore?

Me: Carl Sagan also said, “science today is the way of thinking much more than it is the body of knowledge.” The processes that I adopt and the rationale behind my current research is pure science. And, might I add that whilst my research is important to me, what is even more important to me is knowing that I am responsible for actively ensuring that society is better able to understand the effects of science, both positive and negative. To me that is worth far more than a few dozen citations and a slight bump in my h-index.

Pause

Random: You had me at Carl Sagan.

Sam Illingworth is a lecturer in Science Communication at Manchester Metropolitan University in the UK. His research involves looking at the ways in which science interacts with society via different cultural media. When he is not doing that he likes to write bad poems about good science, some of which can be read here.

Sam Illingworth is a lecturer in Science Communication at Manchester Metropolitan University in the UK. His research involves looking at the ways in which science interacts with society via different cultural media. When he is not doing that he likes to write bad poems about good science, some of which can be read here.

Twitter: @samillingworth

[…] PLOS BLOGS welcomes Sam Illingworth, a professor of physics and science communications, with this guest post. Read his full bio below. By Sam Illingworth This is a snippet from a recent dinner party conversation: Random: So, what job do you do? Me: … Continue reading » […]

Lovely blog – thanks for sharing this experience! It’s good to think about ways of positioning the strategic importance of public science communication in casual conversations, but also in formal contexts. I’ve just started in a new position as science communication researcher/lecturer at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. We also have to be able to “defend” the strategic importance of social science research and closer collaboration between natural and social science researchers – especially in the field of science communication.

Thanks Marina!

I would be very interested to hear about how you get on in your new position, as I think that the link up between social science researchers, natural scientists and science communicators is very important, especially in terms of science policy.

Sam

Some valid points – but frankly, science communication or scientific communication as a job or as a topic of research are two very different things. There is a large dose of plain old marketing and mass communication (ie non-science) in a lot of activities badged as “scicomm” jobs.

During more than a decade of work experience devoted to scicomm, being made to feel like I was somehow a rank or two below being “a scientist” was not uncommon. This always surprised me because essentially I was viewed as being there to get their work published and therefore increase the visibility of both the individual researcher and the institution. A sort of glorified secretary.

The scientific ego has never been comfortable with someone else, an “outsider” being able to understand and translate their work. One of the perverse outcomes of the use of IF to rank researchers has been that the kind of uniqueness which gets brownie points from news organizations has become an important criteria for researchers. This has been interpreted by some to mean that only “I” can possibly understand what I do (e.g. the recent objections to replicating cancer research publicized in Science just a few days ago, http://news.sciencemag.org/biology/2015/06/feature-cancer-reproducibility-effort-faces-backlash). And it is doing damage to the scientific method itself, which depends on replication and not one offs that capture headlines.

Ironically, since my primary task involved revising manuscripts for any research group onsite – I was possibly more widely read than many of the authors I worked for. For example, I launched a program to replace historical scientific results in modern research questions. Despite incredible positive experiences which opened new avenues of dissemination between multiple research groups, this program was killed by the institution and I then realized that my job was only perceived as “spellchecking” and “making logos”.

People working in science communication move fluidly between disciplines and often have a rather privileged and unique birds-eye view of scientific practice in numerous fields. This alone means these persons can offer valuable insights on diverse aspects institutional policies for example. But if the institutional support is not there – scicomm people will not only fail, they will leave and take all their valuable experience to a competitor.

PS happily I have transitioned back to research and my project remains alive as a doctoral research project at another institution.

EXCELLENT piece. I couldn’t agree more, and I could not possibly have said it better myself. In the 10 years since I was an undergraduate, first deciding that I would be pursuing a biochemistry major and all the subsequent career goals of a scientist, I have had many conversations with non-scientists that contain equally facepalm-worthy punchlines. It is quite alarming the fraction of the public who is, for all intents and purposes, effectively science-illiterate.

While my close friends don’t fall into this category (likely because they hold comparable levels of education to myself), I still end up frequently speaking to people who are absurdly impressed when I tell them what I do. And they are totally sincere about it too–I know because I get very embarrassed when people pay me undeserved praise. I’ve gotten used to it now, but so many people freely demonstrate their perception that a clearly marked delineation exists between all things “science” vs everything else in life they know and can learn about.

This prevalent belief that anyone who is a scientist must be some kind of mad 1-in-a-million genius always baffled me. Don’t get me wrong, some of the smartest people i’ve ever met were colleagues or professors I had — but at the same time, some of the most memorable idiots I’ve ever had the pleasure of interacting with, also came from this same pool of people. So many people assume and operate from an early age under the assumption that math and science are out-of-the-question too difficult for them to even attempt. Because of this, many people don’t bother to even try to understand common scientific principles that they come into contact with in their regular life. This has real-world consequences too, things which I won’t get into here because they often turn into science vs politics debates (which by definition, demonstrates this problem perfectly)

—-

This is why science communication is so important. The public, given the current state of our culture, is NOT going to take it upon themselves to rectify the problem on their own. We who are already in science need to be the movers and the shakers.

I am not currently involved in the field, but I have long held the hope that some day I could transition into it. Maybe be the world’s next Bill Nye the science guy or Neil DeGrasse Tyson. I hesitate writing this while giving my real name though, because just as the author of this piece suggests, this admission could potentially cause colleagues to look down their nose at me for it.

Anyhoo, absolutely LOVE the article. Keep on fighting the good fight.

[i][b]Science isn’t the body of knowledge that we currently hold, it is the method by which we learned it. [/i][/b]